Showing posts with label Nigeria. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Nigeria. Show all posts

Thursday, January 17, 2013

OGPSS - Miles travelled, gas used and OPEC

Leanan has noted the API report of the continuing drop in US oil demand. It would be wrong, I believe, to explain this purely by reference to the increased efficiency of vehicles now on the road, nor would it be realistic to expect that these changing conditions will result in a lowering of gas prices.

To explain the rationale behind these thoughts requires reference to two sets of data. The most potent is the behavior of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), but before discussing their actions the story begins with the changes in the miles travelled reports that are issued by the Federal Highway Administration each month. Driven by a comment on recent versions of that plot, it is worth revisiting the summary of the rolling total of miles travelled in the United States, with the October 2012 plot being the last available.

Figure 1. 12 month rolling total of miles driven on all roads in the United States (FHWA) It should be noted that this is not the amount of fuel used, but rather the distance travelled, and thus in itself this does not reflect any changes in vehicle performance because of the increased efficiency of their engines. And while there does not appear to be any great difference between the numbers for 2011 and 2012 when broken down by month, for rural and urban travel, they both lie below the values for 2010.

Figure 2. Travel on US Urban Highways by Month (FHWA)

Figure 3. Travel on US Rural Highways by month (FHWA) This shows that folk are actually driving less than they have previously, which may be reflective of the current economic condition, when combined with the high price for gasoline in relative historic terms. One can compare these curves with the demand for gasoline from This Week in Petroleum., though this has data through the end of the year and has a slightly different lower scale range.

Figure 4, Demand for gasoline in the United States (EIA TWIP) Demand for gasoline, as with miles travelled, seems relatively equivalent for data for 2011 and 2012. The demand for ethanol, on the other hand, seems to be significantly less, assuming production matches that demand.

Figure 5. Production of fuel ethanol in the United States (EIA TWIP) OPEC take a keen interest in those activities in the United States that impact the demand for oil, and in their latest Monthly Oil Market Report (MOMR) have plotted the variation in oil price with miles driven:

Figure 6. US mileage plotted against the retail price of gasoline (OPEC January MOMR) Driven by increased demands for vehicular fuel OPEC anticipates continued growth in domestic demand for oil, both in the Middle East, and in Latin America.

Figure 7. Increase in domestic oil demand in the Middle East over 2012 and 2013. (OPEC January MOMR)

Figure 8. Anticipated growth in domestic demand in Latin America (OPEC MOMR) Both of these tables feed into and support the position that Westexas has discussed in regard to the drop in available exports of oil in the coming years. OPEC is not expecting to increase production in the coming year, but rather expecting that increase in demand will be met by production growth from the non-OPEC nations with numbers similar to those discussed earlier. And, as noted, most of that production growth is expected to come from America. The report confirms that OPEC, and particularly Saudi Arabia is willing to cut production, when demand falls, so that price levels are sustained. As in previous months the numbers showing production differ when the reports come from the countries themselves in contrast with reports from secondary sources.

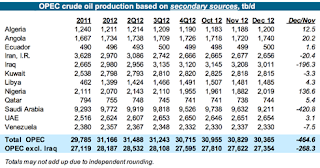

Figure 9. OPEC crude production as reported directly. (OPEC MOMR ) There are significant drops in production reported for Iraq, Libya, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia so that the reported drop in production comes close to 1 mbd. There is not quite the same amount of sacrifice evident in the numbers from secondary sources.

Figure 10. OPEC crude production as reported from secondary sources (OPEC MOMR ) Overall production is down only around 500 kbd, with almost all of that being a reduction from Saudi Arabia. The difference between the production numbers from Nigeria (they report cutting production 120 kbd while others report they have increased production 136 kbd) are perhaps indicative of some of the problems that exist within the OPEC organization when they try and balance the supply:demand equation. However, given that KSA is willing to do the heavy lifting it seems likely that prices will continue at their current levels, despite any changes in American production levels.

Figure 1. 12 month rolling total of miles driven on all roads in the United States (FHWA) It should be noted that this is not the amount of fuel used, but rather the distance travelled, and thus in itself this does not reflect any changes in vehicle performance because of the increased efficiency of their engines. And while there does not appear to be any great difference between the numbers for 2011 and 2012 when broken down by month, for rural and urban travel, they both lie below the values for 2010.

Figure 2. Travel on US Urban Highways by Month (FHWA)

Figure 3. Travel on US Rural Highways by month (FHWA) This shows that folk are actually driving less than they have previously, which may be reflective of the current economic condition, when combined with the high price for gasoline in relative historic terms. One can compare these curves with the demand for gasoline from This Week in Petroleum., though this has data through the end of the year and has a slightly different lower scale range.

Figure 4, Demand for gasoline in the United States (EIA TWIP) Demand for gasoline, as with miles travelled, seems relatively equivalent for data for 2011 and 2012. The demand for ethanol, on the other hand, seems to be significantly less, assuming production matches that demand.

Figure 5. Production of fuel ethanol in the United States (EIA TWIP) OPEC take a keen interest in those activities in the United States that impact the demand for oil, and in their latest Monthly Oil Market Report (MOMR) have plotted the variation in oil price with miles driven:

Figure 6. US mileage plotted against the retail price of gasoline (OPEC January MOMR) Driven by increased demands for vehicular fuel OPEC anticipates continued growth in domestic demand for oil, both in the Middle East, and in Latin America.

Figure 7. Increase in domestic oil demand in the Middle East over 2012 and 2013. (OPEC January MOMR)

Figure 8. Anticipated growth in domestic demand in Latin America (OPEC MOMR) Both of these tables feed into and support the position that Westexas has discussed in regard to the drop in available exports of oil in the coming years. OPEC is not expecting to increase production in the coming year, but rather expecting that increase in demand will be met by production growth from the non-OPEC nations with numbers similar to those discussed earlier. And, as noted, most of that production growth is expected to come from America. The report confirms that OPEC, and particularly Saudi Arabia is willing to cut production, when demand falls, so that price levels are sustained. As in previous months the numbers showing production differ when the reports come from the countries themselves in contrast with reports from secondary sources.

Figure 9. OPEC crude production as reported directly. (OPEC MOMR ) There are significant drops in production reported for Iraq, Libya, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia so that the reported drop in production comes close to 1 mbd. There is not quite the same amount of sacrifice evident in the numbers from secondary sources.

Figure 10. OPEC crude production as reported from secondary sources (OPEC MOMR ) Overall production is down only around 500 kbd, with almost all of that being a reduction from Saudi Arabia. The difference between the production numbers from Nigeria (they report cutting production 120 kbd while others report they have increased production 136 kbd) are perhaps indicative of some of the problems that exist within the OPEC organization when they try and balance the supply:demand equation. However, given that KSA is willing to do the heavy lifting it seems likely that prices will continue at their current levels, despite any changes in American production levels.

Read more!

Monday, November 14, 2011

OGPSS - gas flares, their significance in Russia

Over the weekend I went to a talk on the promise of shale oil and gas, given by Sid Green, a friend and one of those members of the National Academy with Washington influence in regard to the future of the fossil fuel business. (He appears much more a Yerginite than a follower of Matt Simmons, as was evident by his conclusion that the fuels from the shale deposits of the country will be our short-term savior. This is a proposition that I have provided some evidence to doubt). However it was in his introduction, by Joseph Smith, the new Laufer Chair of Energy at MS&T, that a slide appeared that is useful to preface where this, the Tech Talk series, will go next. This is the slide:

A poster from NOAA showing the light emitted at night from city lights (white), fires (red), boats are in blue and gas flares are in green. (The picture was put together over the period from January to December 2003.)

A poster from NOAA showing the light emitted at night from city lights (white), fires (red), boats are in blue and gas flares are in green. (The picture was put together over the period from January to December 2003.)

It was that large green blob sitting just below the Yamal Peninsula in Russia that caught my eye. It shows the volume of stranded natural gas in Russia that is being flared off because it is stranded, i.e. there is no current way to ship it to market.

UPDATE: I have changed the end of the post to reflect a written answer to my question from Sid Green.

Interestingly, given that preponderance of flaring in Russia, one can also go to a paper given at a Russian meeting where the more ubiquitous size of gas flaring operations around the world is more evident.

City Lights and gas flares around the world, data collected In 1994-95. (city lights in grey, flares in red).

City Lights and gas flares around the world, data collected In 1994-95. (city lights in grey, flares in red).

As I noted in a recent post on developments in the Bakken shale, up to 30% of the natural gas that is being produced with the oil is being flared at the moment because there is no way of getting it to market. (And in 1994, note the amount being flared in the North Sea). It is not just a problem for large wells, For many years I drove between Rolla, MO and Crane, IN, spending the night in Vincennes, usually arriving late, with my drive through Eastern Illinois illuminated by flares from the small stripper wells along the way. And it is possible to see flares from the rigs operating in the Gulf of Mexico.

Gas flares illuminating the night in the Gulf of Mexico (NOAA)

Gas flares illuminating the night in the Gulf of Mexico (NOAA)

In the past Gregor Macdonald has also documented the flares that are found off the coast of Nigeria. . And there was some suspicion that these represented the greatest volume of gas being burned off in this way.

Flares around Nigeria color coded by duration, Those active in 2006 and 2000 are yellow. Those active in 2000 but not 1992 or 2006 are green. Those active in 1992 but not 2000 or 2006 are blue. (NOAA )

Flares around Nigeria color coded by duration, Those active in 2006 and 2000 are yellow. Those active in 2000 but not 1992 or 2006 are green. Those active in 1992 but not 2000 or 2006 are blue. (NOAA )

A 2007 survey, carried out by NOAA for the World Bank, showed that Russia was burning roughly twice the volume of gas as that lost in Nigeria. A close look shows how the plumes from the flares dominate the Siberian night-time sky.

Thermal plumes from gas flares in Siberia

Thermal plumes from gas flares in Siberia

The NOAA report indicates that around 160 billion cubic meters of gas is flared each year, roughly a quarter of the volume of natural gas that is used in the United States each year. And while countries such as Nigeria have been able to reduce the amount that is flared, countries such as Russia, Kazakhstan and Iraq have increased the volumes flared. (It also explains how the images above were generated). The region of Russia with the most gas flaring is that around the Khanty-Mansiysk region, which accounts for roughly half the Russian total. In 2007 a conference on the subject heard that Russia was flaring around 50 bcm per yer, with Khanty-Mansiysk contributing 24 bcm of this total. (The gas is flared because this is currently where about half of Russia’s oil production is coming from). At that time the goal was set that, by the end of this year, (2011) some 95% of this natural gas should be utilized. There have been a variety of ways suggested to reach that goal. Again, putting the volumes in context, Russia commercially produced some 600 bcm of natural gas in 2006, as well as some 10 million barrels of oil a day.

Flaring around the Khanty-Manysiyski region south and east of Yamal. (World Bank)

Flaring around the Khanty-Manysiyski region south and east of Yamal. (World Bank)

At present Russia has reached a new peak in crude oil production of some 10.34 mbd for October, while Saudi production is estimated to have risen to 9.8 mbd. Russia is thus the current largest oil producer, and so it is time to look at where (other than just the region shown above) the oil is coming from, and what the prospects for the future hold for the longer term production, and export of energy from that country.

The natural gas production picture is not quite that rosy, even with the reduction in gas flaring that has been undertaken. Gazprom is reported to have reduced supply as prices in Europe have risen towards $15 per kcf (thousand cubic feet), almost four times that of gas in the United States. Russia as a whole produced some 1.8 bcm/day (63 bcf) of which Gazprom produced 1.35 bcm, both figures down from the same time last year. At the same time domestic consumption of natural gas has risen by some 1.3 bcf/day. Russia supplies about a quarter of European demand, and as production falls off in some of the fields of Western Europe that portion may increase. However the global supply of natural gas is still quite healthy with countries seeking to find domestic sources from the gas shales that might lower their import needs. Thus the power that Gazprom was able to wield just a couple of years ago has now been somewhat reduced.

All of these factors strengthen the conclusion that this series should now move to look at some of the fields in Russia, and given that Dr Yergin has proved to be a better historian than prophet, that probably means that I should go away and re-read The Prize, before it starts. (Though The Quest is an easier read). After all, one wonders how many of us, a week ago, could have found Khanty-Manysiyski on a map?

Location of Khanty-Manysiyski on a map of Russia (Google Earth)

Location of Khanty-Manysiyski on a map of Russia (Google Earth)

In passing, Secretary Salazar has just announced that permitting will allow the Natural Buttes Project to move forward. Anadarko are expected to develop up to 3,675 wells in the Uintah Basin over the next decade to supply more cheap natural gas into the market, and likely keep the price pressure on the production of gas from gas shales. Which brings me full circle back to the opening of the post, since the question that I asked Sid at the presentation was “How long can the gas shale companies afford to sell their gas at under $4 per kcf, when it is costing them more than this to produce it?”

UPDATE: I had a short snippy version of Sid's reply here, but he was kind enough to send a critique and deeper explanation, which gives a better answer. To summarize his answer, he feels very much in agreement with the points that Rockman has been making in comments on a number of my posts on this topic.

He notes that financing for the E&P companies has recently largely come from "venture capital" money. The companies are able to recover much of their own capex in the first months, but he was careful to note that this did not imply that they are able to make a profit. And with that return they are able to continue on the “tread mill” of drilling another well, and another . . . .

He quoted costs, and noted that a recent WSJ article said that Pioneer was reported to have costs of around $2.48 per kcf. Though if I can interject they are drilling the Eagle Ford and thus the costs may be lower for the gas, since they are, as he notes, making most of the money from the associated liquids. (And Rockman is not that excited about the general situation down there).

However he thinks Haynesville costs are up to $3.50 and Marcellus up to $4.00 or more per kcf. As a result the number of rigs might soon start falling, though he has hopes that with some technical improvements the cost figures might come under better control, and he senses that there are others in the industry also anticipating greater production at lower cost, with some of the better ideas that are being developed. These relate (HO thinks) to better control of the fracture paths induced out into the formations. But without much change operations will move over to more liquid productive areas, and the natural gas situation will not be sustainable as it is.

As an additional side comment there are now animated maps of the Barnett, Bakken and Eagle Ford plays, showing the wells drilled each year, and the production totals, under the Shale Play Development History Animationssections of the EIA map page. (H/t this weeks TWIP which is on the Bakken andEagle Ford.)

A poster from NOAA showing the light emitted at night from city lights (white), fires (red), boats are in blue and gas flares are in green. (The picture was put together over the period from January to December 2003.)

A poster from NOAA showing the light emitted at night from city lights (white), fires (red), boats are in blue and gas flares are in green. (The picture was put together over the period from January to December 2003.)It was that large green blob sitting just below the Yamal Peninsula in Russia that caught my eye. It shows the volume of stranded natural gas in Russia that is being flared off because it is stranded, i.e. there is no current way to ship it to market.

UPDATE: I have changed the end of the post to reflect a written answer to my question from Sid Green.

Interestingly, given that preponderance of flaring in Russia, one can also go to a paper given at a Russian meeting where the more ubiquitous size of gas flaring operations around the world is more evident.

City Lights and gas flares around the world, data collected In 1994-95. (city lights in grey, flares in red).

City Lights and gas flares around the world, data collected In 1994-95. (city lights in grey, flares in red).As I noted in a recent post on developments in the Bakken shale, up to 30% of the natural gas that is being produced with the oil is being flared at the moment because there is no way of getting it to market. (And in 1994, note the amount being flared in the North Sea). It is not just a problem for large wells, For many years I drove between Rolla, MO and Crane, IN, spending the night in Vincennes, usually arriving late, with my drive through Eastern Illinois illuminated by flares from the small stripper wells along the way. And it is possible to see flares from the rigs operating in the Gulf of Mexico.

Gas flares illuminating the night in the Gulf of Mexico (NOAA)

Gas flares illuminating the night in the Gulf of Mexico (NOAA)In the past Gregor Macdonald has also documented the flares that are found off the coast of Nigeria. . And there was some suspicion that these represented the greatest volume of gas being burned off in this way.

Flares around Nigeria color coded by duration, Those active in 2006 and 2000 are yellow. Those active in 2000 but not 1992 or 2006 are green. Those active in 1992 but not 2000 or 2006 are blue. (NOAA )

Flares around Nigeria color coded by duration, Those active in 2006 and 2000 are yellow. Those active in 2000 but not 1992 or 2006 are green. Those active in 1992 but not 2000 or 2006 are blue. (NOAA )A 2007 survey, carried out by NOAA for the World Bank, showed that Russia was burning roughly twice the volume of gas as that lost in Nigeria. A close look shows how the plumes from the flares dominate the Siberian night-time sky.

Thermal plumes from gas flares in Siberia

Thermal plumes from gas flares in SiberiaThe NOAA report indicates that around 160 billion cubic meters of gas is flared each year, roughly a quarter of the volume of natural gas that is used in the United States each year. And while countries such as Nigeria have been able to reduce the amount that is flared, countries such as Russia, Kazakhstan and Iraq have increased the volumes flared. (It also explains how the images above were generated). The region of Russia with the most gas flaring is that around the Khanty-Mansiysk region, which accounts for roughly half the Russian total. In 2007 a conference on the subject heard that Russia was flaring around 50 bcm per yer, with Khanty-Mansiysk contributing 24 bcm of this total. (The gas is flared because this is currently where about half of Russia’s oil production is coming from). At that time the goal was set that, by the end of this year, (2011) some 95% of this natural gas should be utilized. There have been a variety of ways suggested to reach that goal. Again, putting the volumes in context, Russia commercially produced some 600 bcm of natural gas in 2006, as well as some 10 million barrels of oil a day.

Flaring around the Khanty-Manysiyski region south and east of Yamal. (World Bank)

Flaring around the Khanty-Manysiyski region south and east of Yamal. (World Bank)At present Russia has reached a new peak in crude oil production of some 10.34 mbd for October, while Saudi production is estimated to have risen to 9.8 mbd. Russia is thus the current largest oil producer, and so it is time to look at where (other than just the region shown above) the oil is coming from, and what the prospects for the future hold for the longer term production, and export of energy from that country.

The natural gas production picture is not quite that rosy, even with the reduction in gas flaring that has been undertaken. Gazprom is reported to have reduced supply as prices in Europe have risen towards $15 per kcf (thousand cubic feet), almost four times that of gas in the United States. Russia as a whole produced some 1.8 bcm/day (63 bcf) of which Gazprom produced 1.35 bcm, both figures down from the same time last year. At the same time domestic consumption of natural gas has risen by some 1.3 bcf/day. Russia supplies about a quarter of European demand, and as production falls off in some of the fields of Western Europe that portion may increase. However the global supply of natural gas is still quite healthy with countries seeking to find domestic sources from the gas shales that might lower their import needs. Thus the power that Gazprom was able to wield just a couple of years ago has now been somewhat reduced.

All of these factors strengthen the conclusion that this series should now move to look at some of the fields in Russia, and given that Dr Yergin has proved to be a better historian than prophet, that probably means that I should go away and re-read The Prize, before it starts. (Though The Quest is an easier read). After all, one wonders how many of us, a week ago, could have found Khanty-Manysiyski on a map?

Location of Khanty-Manysiyski on a map of Russia (Google Earth)

Location of Khanty-Manysiyski on a map of Russia (Google Earth)In passing, Secretary Salazar has just announced that permitting will allow the Natural Buttes Project to move forward. Anadarko are expected to develop up to 3,675 wells in the Uintah Basin over the next decade to supply more cheap natural gas into the market, and likely keep the price pressure on the production of gas from gas shales. Which brings me full circle back to the opening of the post, since the question that I asked Sid at the presentation was “How long can the gas shale companies afford to sell their gas at under $4 per kcf, when it is costing them more than this to produce it?”

UPDATE: I had a short snippy version of Sid's reply here, but he was kind enough to send a critique and deeper explanation, which gives a better answer. To summarize his answer, he feels very much in agreement with the points that Rockman has been making in comments on a number of my posts on this topic.

He notes that financing for the E&P companies has recently largely come from "venture capital" money. The companies are able to recover much of their own capex in the first months, but he was careful to note that this did not imply that they are able to make a profit. And with that return they are able to continue on the “tread mill” of drilling another well, and another . . . .

He quoted costs, and noted that a recent WSJ article said that Pioneer was reported to have costs of around $2.48 per kcf. Though if I can interject they are drilling the Eagle Ford and thus the costs may be lower for the gas, since they are, as he notes, making most of the money from the associated liquids. (And Rockman is not that excited about the general situation down there).

However he thinks Haynesville costs are up to $3.50 and Marcellus up to $4.00 or more per kcf. As a result the number of rigs might soon start falling, though he has hopes that with some technical improvements the cost figures might come under better control, and he senses that there are others in the industry also anticipating greater production at lower cost, with some of the better ideas that are being developed. These relate (HO thinks) to better control of the fracture paths induced out into the formations. But without much change operations will move over to more liquid productive areas, and the natural gas situation will not be sustainable as it is.

As an additional side comment there are now animated maps of the Barnett, Bakken and Eagle Ford plays, showing the wells drilled each year, and the production totals, under the Shale Play Development History Animationssections of the EIA map page. (H/t this weeks TWIP which is on the Bakken andEagle Ford.)

Read more!

Labels:

gas flare,

GOM,

Khanty-Manysiyski,

Natural gas,

Nigeria,

Russia,

Russian production

Sunday, April 3, 2011

OGPSS - The top 30 oil producers, a review

These posts have been going through the EIA list of the top oil producers in the world, over the past few weeks, I thought I might just review them collectively, but briefly, before starting to look at individual countries and oilfields. Even the posts that I have written recently have become out of date with new information (Russia increased production again in February by 20 kbd over January reaching 10.23 mbd) and then fell back to 10.2 mbd in March but at this stage, rather than focusing on such details, I am trying to generate a sense of the overall picture. It should also be recognized that I am just grabbing a snapshot of data, rather than the more detailed studies that look at the longer term, which folk such as Rembrandt, Rune and Euan provide. The simplest way to do this is to place my current estimates of production for the top 30 oil producers that I have reviewed in this series against the EIA estimate of their production in 2009.

Top 30 oil producing countries (those increasing production over 2009 are shown in red). (Click on the table to enlarge it)

Top 30 oil producing countries (those increasing production over 2009 are shown in red). (Click on the table to enlarge it)

It is significant to note that while Saudi Arabia was producing 8.05 mbd of crude in 2009, this has risen to 8.869 mbd on average for February as the Kingdom increased production to match the shortfalls in oil exports from Libya, inter alia. (With roughly 1.8 mbd in “other liquids” this takes total KSA production to 10.67 mbd and moves it back to the top of the League. However those numbers were from the March MOMR, which reports on February, In that report Libya was still being recorded as producing around 1.3 mbd). It is now reported that overall OPEC was not able to match the Libyan decline in March, falling about 350 kbd short, while KSA production has now reached 9 mbd, (10.8 including other liquids).

Contrary to President Obama’s recent remarks the EIA are anticipating a decline in US crude oil and liquids production over the next two years, part of which has been blamed on the change in GOM regulations. As a result it would be optimistic to anticipate much more than a US production of 8.3 mbd (and the EIA project it will be down to 8.2 mbd next year). It is unlikely that US production will increase beyond that point.

US crude and liquid fuels production – (EIA )

US crude and liquid fuels production – (EIA )

With China, Iran, and Canada holding relatively steady in the short term, this gives an updated total of 39.83 mbd for the top six, which is about 1.4 mbd higher than when I wrote the initial post back in February, but 500 kbd below the EIA estimate for their 2009 production. (While Russia and the KSA increased, the USA and Iran declined). Of these it is likely that only the KSA can continue to increase production much more.

In the second tier, Mexican production continues to fall, and was down to 2.556 mbd in February, with reports that it will now be an oil importer well before 2020. Exports have already fallen to 1.23 mbd, which does not bode well for customers. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) have, like the KSA, increased production to help out, though so far this has only been up to 2.394 mbd from 2.3 mbd for most of last year. (They also produce roughly another 500 kbd of other liquid fuels). By 2020 they should be able to produce up to 3.5 mbd. And in similar vein Kuwait, now producing at 2.368 mbd, up from 2,3 mbd. Kuwaiti plans are to reach 3.5 mbd by 2015, and be at 4 mbd by 2020.

The current political turmoil has even persuaded Venezuela to increase production, with OPEC reporting levels of 2.39 mbd for February, a gain of around 100 kbd. Though how long that is sustained depends on the success of the many investors that have been persuaded to invest in the Venezuelan oil sands.

In the third group Norway is declining, being now at just over 2 mbd, and even though it has just announced a major new discovery that will not come on line for at least 5 – 10 years, and in the meanwhile production will continue to fall. Norway needs more discoveries similar to this, however, to be able to sustain production levels extending into the future, since without them production will collapse.

Brazil was touted, by President Obama in his remarks about the Energy Blueprint last week, though the increasing volumes of oil that they will produce remain foreign to the United States, and though they will likely increase production up to around 4 mbd by 2020, rising domestic consumption may well take much of that increase.

Which brings us into the states that has some political turmoil. Iraq has been able to bring production back to around 2.64 mbd (according to OPEC) with the hope of reaching 3 mbd by the end of this year. At the moment about 1.2 mbd of this is exported. One of the great questions of the decade is just how close to a projected 10 mbd by 2020 that Iraq will be able to get. Sadly the continuing conflicts there, though reduced in scale, make it difficult for me to see much beyond 5 mbd by 2020.

Nigeria, which has had its own internal conflicts for some time, is going to the polls as I write this, and the expected winner is planning to overhaul the oil industry. However, if stability continues, then it might be possible to resurrect some of the older fields and perhaps increase overall production by some 350 kbd.

Algeria, which has had some turmoil, but may emerge from the ongoing protests without much change, is producing around 2 mbd of liquids. That has not changed as OPEC has moved to match the decline in volumes from Libya and other countries facing protests, and may reflect the current maximum that the country can produce. In the stability stakes I suspect that Algeria may survive without much change, although the plot I put up from Energy Export Databrowser does suggest that production may have peaked.

Algerian oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser)

Algerian oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser)

Angola is currently producing 1.7 mbd but may add some 650 kbd this year, for a total of 2.35 mbd. And that brings us to Libya, where the increased fighting, particularly over the oil refinery town of Ras Lanuf, makes it increasingly unlikely that the 1.7 mbd which came from Libya will be available again soon.

The United Kingdom is in significant decline, but recent moves to further tax the oil industry have made it possible that the decline may steepen. This because the new taxes proposed will likely reduce the profitability of the field developments proposed, discouraging their development. Recently production has run at 1.35 mbd of liquids, which is scheduled to drop to 1.3 mbd this year, and 0.94 mbdoe of natural gas, anticipated to fall to 0.85 mbdoe this year. The criticality of investment is shown in the projected production over the next 5 years, with the different colors showing the likelihood of success. Note that the grey of current production is declining at about 10%.

UK Projected Oil production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey )

UK Projected Oil production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey )

UK Projected Natural Gas production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey )

UK Projected Natural Gas production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey )

Moving to the next tier down, Kazakhstan is now at 1.6 mbd and slowly increasing production toward a target of 3 mbd by 2020. Qatar is running at 1.4 mbd, but with almost 0.6 mbd of that in NGL. Indonesia is producing right around 1 mbd and may maintain that in the short term. It is being challenged in rank by Azerbaijan which has just incremented up to 1 mbd, a volume that is expected to continue to rise until it reaches about 1.25 mbd in 2014.

The tier that lies below 1 mbd starts with India, which is currently holding a production of around 878 kbd, and having to import increasing amounts of oil to meet demand. Given that the country also subsidizes the price, this is becoming an increasingly expensive consideration for the government. India is followed by Argentina, which is post peak and declined to 0.76 mbd most recently. Egypt is similarly declining, now to 660 kbd, but as one of the early nations to change under the most recent protests, and with the situation still somewhat fluid, it is difficult to predict how much the country will have both for itself, and for external customers, a year from now.

Oman will likely weather the current storms, and is also increasing oil production, to the point that it is moving up to pass India, with an Omani production of 863 kbd, some of which is tied to NGL production.

In the final four that produce more than 500 kbd Malaysia is barely maintaining production at 700 kbd, while Australia has fallen from 588 kbd to 540 kbd. Both are now being passed in production by Colombia, one of the “hotter” places for development at the moment, with production rising to possibly 920 kbd this year. Ecuador, which closes out the top 30, has recently increased production from 485 to 504 kbd.

That completes the top 30, and accounts for some 76.7 mbd of production. Those same countries back in 2009 were reported by the EIA as producing some 79.23 mbd of oil. Remember that world demand is anticipated to increase by somewhere between 1.4 and 1.6 mbd this year, and that of this list of 30 only 13 increased production, and the rest declined and the concern for the future becomes thus more clearly defined. (The difference between the two totals is partially explained by the loss in Libyan oil - we will see within the month how well OPEC covers that).

But it is not the overall production from the world that can be estimated that accurately, but by looking at individual countries and, in some cases, individual oilfields that we can get some better sense of what is to come. So the next step will be looking at these nations in more detail, in the weeks ahead.

Top 30 oil producing countries (those increasing production over 2009 are shown in red). (Click on the table to enlarge it)

Top 30 oil producing countries (those increasing production over 2009 are shown in red). (Click on the table to enlarge it)It is significant to note that while Saudi Arabia was producing 8.05 mbd of crude in 2009, this has risen to 8.869 mbd on average for February as the Kingdom increased production to match the shortfalls in oil exports from Libya, inter alia. (With roughly 1.8 mbd in “other liquids” this takes total KSA production to 10.67 mbd and moves it back to the top of the League. However those numbers were from the March MOMR, which reports on February, In that report Libya was still being recorded as producing around 1.3 mbd). It is now reported that overall OPEC was not able to match the Libyan decline in March, falling about 350 kbd short, while KSA production has now reached 9 mbd, (10.8 including other liquids).

Contrary to President Obama’s recent remarks the EIA are anticipating a decline in US crude oil and liquids production over the next two years, part of which has been blamed on the change in GOM regulations. As a result it would be optimistic to anticipate much more than a US production of 8.3 mbd (and the EIA project it will be down to 8.2 mbd next year). It is unlikely that US production will increase beyond that point.

US crude and liquid fuels production – (EIA )

US crude and liquid fuels production – (EIA ) With China, Iran, and Canada holding relatively steady in the short term, this gives an updated total of 39.83 mbd for the top six, which is about 1.4 mbd higher than when I wrote the initial post back in February, but 500 kbd below the EIA estimate for their 2009 production. (While Russia and the KSA increased, the USA and Iran declined). Of these it is likely that only the KSA can continue to increase production much more.

In the second tier, Mexican production continues to fall, and was down to 2.556 mbd in February, with reports that it will now be an oil importer well before 2020. Exports have already fallen to 1.23 mbd, which does not bode well for customers. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) have, like the KSA, increased production to help out, though so far this has only been up to 2.394 mbd from 2.3 mbd for most of last year. (They also produce roughly another 500 kbd of other liquid fuels). By 2020 they should be able to produce up to 3.5 mbd. And in similar vein Kuwait, now producing at 2.368 mbd, up from 2,3 mbd. Kuwaiti plans are to reach 3.5 mbd by 2015, and be at 4 mbd by 2020.

The current political turmoil has even persuaded Venezuela to increase production, with OPEC reporting levels of 2.39 mbd for February, a gain of around 100 kbd. Though how long that is sustained depends on the success of the many investors that have been persuaded to invest in the Venezuelan oil sands.

In the third group Norway is declining, being now at just over 2 mbd, and even though it has just announced a major new discovery that will not come on line for at least 5 – 10 years, and in the meanwhile production will continue to fall. Norway needs more discoveries similar to this, however, to be able to sustain production levels extending into the future, since without them production will collapse.

Brazil was touted, by President Obama in his remarks about the Energy Blueprint last week, though the increasing volumes of oil that they will produce remain foreign to the United States, and though they will likely increase production up to around 4 mbd by 2020, rising domestic consumption may well take much of that increase.

Which brings us into the states that has some political turmoil. Iraq has been able to bring production back to around 2.64 mbd (according to OPEC) with the hope of reaching 3 mbd by the end of this year. At the moment about 1.2 mbd of this is exported. One of the great questions of the decade is just how close to a projected 10 mbd by 2020 that Iraq will be able to get. Sadly the continuing conflicts there, though reduced in scale, make it difficult for me to see much beyond 5 mbd by 2020.

Nigeria, which has had its own internal conflicts for some time, is going to the polls as I write this, and the expected winner is planning to overhaul the oil industry. However, if stability continues, then it might be possible to resurrect some of the older fields and perhaps increase overall production by some 350 kbd.

Algeria, which has had some turmoil, but may emerge from the ongoing protests without much change, is producing around 2 mbd of liquids. That has not changed as OPEC has moved to match the decline in volumes from Libya and other countries facing protests, and may reflect the current maximum that the country can produce. In the stability stakes I suspect that Algeria may survive without much change, although the plot I put up from Energy Export Databrowser does suggest that production may have peaked.

Algerian oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser)

Algerian oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser) Angola is currently producing 1.7 mbd but may add some 650 kbd this year, for a total of 2.35 mbd. And that brings us to Libya, where the increased fighting, particularly over the oil refinery town of Ras Lanuf, makes it increasingly unlikely that the 1.7 mbd which came from Libya will be available again soon.

The United Kingdom is in significant decline, but recent moves to further tax the oil industry have made it possible that the decline may steepen. This because the new taxes proposed will likely reduce the profitability of the field developments proposed, discouraging their development. Recently production has run at 1.35 mbd of liquids, which is scheduled to drop to 1.3 mbd this year, and 0.94 mbdoe of natural gas, anticipated to fall to 0.85 mbdoe this year. The criticality of investment is shown in the projected production over the next 5 years, with the different colors showing the likelihood of success. Note that the grey of current production is declining at about 10%.

UK Projected Oil production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey )

UK Projected Oil production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey ) UK Projected Natural Gas production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey )

UK Projected Natural Gas production (2011 UK Oil and Gas Activity Survey )Moving to the next tier down, Kazakhstan is now at 1.6 mbd and slowly increasing production toward a target of 3 mbd by 2020. Qatar is running at 1.4 mbd, but with almost 0.6 mbd of that in NGL. Indonesia is producing right around 1 mbd and may maintain that in the short term. It is being challenged in rank by Azerbaijan which has just incremented up to 1 mbd, a volume that is expected to continue to rise until it reaches about 1.25 mbd in 2014.

The tier that lies below 1 mbd starts with India, which is currently holding a production of around 878 kbd, and having to import increasing amounts of oil to meet demand. Given that the country also subsidizes the price, this is becoming an increasingly expensive consideration for the government. India is followed by Argentina, which is post peak and declined to 0.76 mbd most recently. Egypt is similarly declining, now to 660 kbd, but as one of the early nations to change under the most recent protests, and with the situation still somewhat fluid, it is difficult to predict how much the country will have both for itself, and for external customers, a year from now.

Oman will likely weather the current storms, and is also increasing oil production, to the point that it is moving up to pass India, with an Omani production of 863 kbd, some of which is tied to NGL production.

In the final four that produce more than 500 kbd Malaysia is barely maintaining production at 700 kbd, while Australia has fallen from 588 kbd to 540 kbd. Both are now being passed in production by Colombia, one of the “hotter” places for development at the moment, with production rising to possibly 920 kbd this year. Ecuador, which closes out the top 30, has recently increased production from 485 to 504 kbd.

That completes the top 30, and accounts for some 76.7 mbd of production. Those same countries back in 2009 were reported by the EIA as producing some 79.23 mbd of oil. Remember that world demand is anticipated to increase by somewhere between 1.4 and 1.6 mbd this year, and that of this list of 30 only 13 increased production, and the rest declined and the concern for the future becomes thus more clearly defined. (The difference between the two totals is partially explained by the loss in Libyan oil - we will see within the month how well OPEC covers that).

But it is not the overall production from the world that can be estimated that accurately, but by looking at individual countries and, in some cases, individual oilfields that we can get some better sense of what is to come. So the next step will be looking at these nations in more detail, in the weeks ahead.

Read more!

Tuesday, March 1, 2011

OGPSS - At around 2 mbd - Nigeria, Angola, Libya and the UK oil production

The growing concerns about the stability of the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) because they make significant contributions to world oil supply adds additional meaning to these weekly posts on the world’s major oil producers. To briefly recap I looked at the top tier oil producers (as listed by the EIA (i.e. those who produce more than 3.1 mbd in 2008) in the first post of the series. (These were Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United States, Iran, China and Canada. ) In the second I looked at the next four countries on the list, namely Mexico, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Kuwait and referred to Venezuela – subject of a series of posts earlier in the year. The third post covered Norway, Brazil, Iraq, and Algeria. And so now we move on to look at Nigeria (2.35 mbd), Angola (2.0 mbd) Libya (1.87 mbd) and the United Kingdom (1.58 mbd). The numbers in parentheses are the production numbers cited by the EIA for 2008. To further put these countries in context, these take us down to number 18 on the list, and with one more post I will have covered all the countries that produced more than 1 mbd on average in 2008.

I will start with Nigeria, which now is cited as producing 2.4 mbd of crude and condensate in January 2011. The country has been having considerable trouble with sabotage and internal unrest, which has had a negative impact on production. However the country signed an Amnesty Program with militants in 2009 which has reduced disruption. As a result in February Nigeria was able to raise production to 2.6 mbd. If this can be sustained it will bring production back over the peak level that was achieved back in 2005.

Note that, for crude oil production alone, Nigeria is listed as producing 2.17 mbd in January, according to the February OPEC MOMR. (Which is also a gain from the above chart). In light of some of my recent comments on who might be hurt if oil production in some of the MENA countries drops off, it is perhaps interesting to note which countries got oil from Nigeria in 2009.

Nigerian oil customers in 2009 (Source EIA )

Nigerian oil customers in 2009 (Source EIA )

Historically Nigeria flared much of the gas that was associated with the oil, particularly in the Niger River Delta, where much of the oil is found. That practice led to some of the more dramatic stories that came from the region, before the amnesty. There is, however, a concerted effort now to capture and market this natural gas, as well as that which comes from gas wells in the country. This has led to some optimism by the Government over future sources of revenue.

There are a total of 6 LNG trains at Finima, on Bonny Island, first coming into production in September 1999, and supplying a variety of customers. While the capacity is at 1.1 Tcf, recent figures have been at about half that volume. (And this is about the same volume that continues to be flared in the country.)

With Nigeria having increased overall production since 2008, though potentially having limited potential for much greater increase, the next country down the list is Angola which, since 2007, is also in OPEC, and OPEC list the January Angolan production of crude at 1.62 mbd. This is significantly below the overall 3.8 mbdoe that BP has reported for total energy production in 2010. Because of some technical problems with water injection, being used to help move oil from the reservoirs, moves to address the problem might overall, reduce the average for 2011 to 3.4 mbdoe. Angola exports about 1. 7 mbd of oil, but is responsive to OPEC requests to control production in order to keep prices at the OPEC comfort level. (Which has risen from around $75 to over $100/bbl in the last few months). Thus the declines shown in the EIA plot below, which only shows through 2009, are more politically induced than due to geological conditions. The EIA, for example, lists project for this year alone that are expected to add 650 kbd to production, and likely export. Unfortunately we are now far enough down the list that while these numbers are significant in their own right, and for the country they may not give that much help to the overall shortages that may evolve over the next year.

Angola currently is building an LNG project at Soyo, expected on stream in 2012 which will handle around 1 bcf/day. Apart from the LNG, which will be exported, the plant will send some 125 mcf/day of natural gas into a distribution network for domestic consumption. Until the plant comes on line most of the almost 1 bcf of natural gas that is produced every day is either flared or reinjected to help with oil production.

Trying to project Libyan future production is rapidly becoming meaningless, I fear as the initial moves to remove the current Leader have not met with sufficient success to eliminate the possibility of civil war. It was only a few weeks ago that Libya was producing at around 1.6 mbd of oil, and Luis de Sousa has reposted an earlier review of the past history of their production. He presciently notes in that post that the rising population of the country is going to demand more of the resource be spent at home. The topic of Libyan production will likely continue to appear in other posts – as it just has – but at the moment it appears, for a variety of reasons, that the system is effectively shut down.

Which brings us to the United Kingdom. Back in the troubled days of the first oil shocks some thirty to forty years ago, it was the combination of new production from the fields in the North Sea and the North Slope that helped bring oil prices down to the low level which allowed the years of growth until now. But we have reached a point where those resources are beginning to disappear, and the UK has turned from an energy exporter to a growing importer. Euan Mearns has documented this progression in a much more detailed and better way than I illuminating, for example, back in 2008, the coming seriousness of their problem.

Euan’s plot of the UK Predicament, from 2008

Euan’s plot of the UK Predicament, from 2008

If we look at the situation today, the reports for last year note

Whether one uses Euan’s plot, or that from the Energy Export Databrowser:

UK Oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser)

UK Oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser)

The UK is clearly entering a more expensive future as it must find more oil from overseas, just as that supply is tightening.

On the other hand, while the situation is getting somewhat worse more rapidly with natural gas, as the EIA plot below shows ( and it contributes to Euan’s total figures) there is a sufficient glut on the world market at the moment that there will not be that immediate a problem in the short-term.

United Kingdom trends in gas statistics (EIA )

United Kingdom trends in gas statistics (EIA )

UPDATE The energy situation in the UK is becoming recognizably more dire, and the Secretary of Climate and Energy, Chris Huhne has just pointed out that the price of $100 a barrel for oil justifies a greater investment in green technology

The current situation in the MENA countries is in such a state of flux, and the impacts barely recognized as yet, that it is becoming even more difficult to have any confidence that the predictions of performance that were being used only a couple of months ago will continue to have much validity in predicting what is likely to occur even in the relatively short term future.

I will start with Nigeria, which now is cited as producing 2.4 mbd of crude and condensate in January 2011. The country has been having considerable trouble with sabotage and internal unrest, which has had a negative impact on production. However the country signed an Amnesty Program with militants in 2009 which has reduced disruption. As a result in February Nigeria was able to raise production to 2.6 mbd. If this can be sustained it will bring production back over the peak level that was achieved back in 2005.

Note that, for crude oil production alone, Nigeria is listed as producing 2.17 mbd in January, according to the February OPEC MOMR. (Which is also a gain from the above chart). In light of some of my recent comments on who might be hurt if oil production in some of the MENA countries drops off, it is perhaps interesting to note which countries got oil from Nigeria in 2009.

Nigerian oil customers in 2009 (Source EIA )

Nigerian oil customers in 2009 (Source EIA ) Historically Nigeria flared much of the gas that was associated with the oil, particularly in the Niger River Delta, where much of the oil is found. That practice led to some of the more dramatic stories that came from the region, before the amnesty. There is, however, a concerted effort now to capture and market this natural gas, as well as that which comes from gas wells in the country. This has led to some optimism by the Government over future sources of revenue.

The Minister also disclosed that the establishment of two new Liquefied Natural Gas, LNG plants, in Olokola in Ogun/Ondo States and Brass LNG in Bayelsa state, will create over 7,000 jobs and inject over $1billion into the host communities.

There are a total of 6 LNG trains at Finima, on Bonny Island, first coming into production in September 1999, and supplying a variety of customers. While the capacity is at 1.1 Tcf, recent figures have been at about half that volume. (And this is about the same volume that continues to be flared in the country.)

With Nigeria having increased overall production since 2008, though potentially having limited potential for much greater increase, the next country down the list is Angola which, since 2007, is also in OPEC, and OPEC list the January Angolan production of crude at 1.62 mbd. This is significantly below the overall 3.8 mbdoe that BP has reported for total energy production in 2010. Because of some technical problems with water injection, being used to help move oil from the reservoirs, moves to address the problem might overall, reduce the average for 2011 to 3.4 mbdoe. Angola exports about 1. 7 mbd of oil, but is responsive to OPEC requests to control production in order to keep prices at the OPEC comfort level. (Which has risen from around $75 to over $100/bbl in the last few months). Thus the declines shown in the EIA plot below, which only shows through 2009, are more politically induced than due to geological conditions. The EIA, for example, lists project for this year alone that are expected to add 650 kbd to production, and likely export. Unfortunately we are now far enough down the list that while these numbers are significant in their own right, and for the country they may not give that much help to the overall shortages that may evolve over the next year.

Angola currently is building an LNG project at Soyo, expected on stream in 2012 which will handle around 1 bcf/day. Apart from the LNG, which will be exported, the plant will send some 125 mcf/day of natural gas into a distribution network for domestic consumption. Until the plant comes on line most of the almost 1 bcf of natural gas that is produced every day is either flared or reinjected to help with oil production.

Trying to project Libyan future production is rapidly becoming meaningless, I fear as the initial moves to remove the current Leader have not met with sufficient success to eliminate the possibility of civil war. It was only a few weeks ago that Libya was producing at around 1.6 mbd of oil, and Luis de Sousa has reposted an earlier review of the past history of their production. He presciently notes in that post that the rising population of the country is going to demand more of the resource be spent at home. The topic of Libyan production will likely continue to appear in other posts – as it just has – but at the moment it appears, for a variety of reasons, that the system is effectively shut down.

Little if any oil can be shipped out of Libya because most ports were closed. Meanwhile, storage tanks were filling up rapidly. Oil traders said one major oil company cargo ship was supposed to berth this week, but no one was at the port to deliver an oil shipment, and shipping companies were reluctant to send ships into the Libyan ports.I have also discussed elsewhere the likelihood of sufficient increase in production in other countries to make up the shortfall. Gazprom has been helping Italy, for example, and Saudi Arabia increasing production, but how long this will last, and how much will ultimately be needed remains an unknown. It really depends on how many dominoes fall, and how long they remain on the table.

Which brings us to the United Kingdom. Back in the troubled days of the first oil shocks some thirty to forty years ago, it was the combination of new production from the fields in the North Sea and the North Slope that helped bring oil prices down to the low level which allowed the years of growth until now. But we have reached a point where those resources are beginning to disappear, and the UK has turned from an energy exporter to a growing importer. Euan Mearns has documented this progression in a much more detailed and better way than I illuminating, for example, back in 2008, the coming seriousness of their problem.

Euan’s plot of the UK Predicament, from 2008

Euan’s plot of the UK Predicament, from 2008 If we look at the situation today, the reports for last year note

In 2010, the UK produced 850 million barrels of oil and gas equivalent (boe) or 2.3 million boe per day. Current plans now target reserves of 11.6 billion boe, 1.3 billion boe more than was anticipated a year ago, reflecting the outcome of increased exploration and appraisal activity across the UKCS and particularly West of Shetland. Oil & Gas UK believes there could be up to 24 billion barrels of oil and gas still to recover from the UKCS.This was about 60% of the UK energy need. Production of crude for last November was 1.047 mbd from offshore, and 9,344 bbl from land wells. The natural gas numbers were 2.7 Bcf from offshore oil wells (as associated gas) and 2.8 Bcf from offshore gas wells. In addition there was some 12 kbd of condensate from the offshore gas fields.

Whether one uses Euan’s plot, or that from the Energy Export Databrowser:

UK Oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser)

UK Oil statistics (Energy Export Databrowser) The UK is clearly entering a more expensive future as it must find more oil from overseas, just as that supply is tightening.

On the other hand, while the situation is getting somewhat worse more rapidly with natural gas, as the EIA plot below shows ( and it contributes to Euan’s total figures) there is a sufficient glut on the world market at the moment that there will not be that immediate a problem in the short-term.

United Kingdom trends in gas statistics (EIA )

United Kingdom trends in gas statistics (EIA ) UPDATE The energy situation in the UK is becoming recognizably more dire, and the Secretary of Climate and Energy, Chris Huhne has just pointed out that the price of $100 a barrel for oil justifies a greater investment in green technology

Drawing on research conducted for the previous government by Lord Stern, Huhne argued that a $100 a barrel price is the exact point at which the economics of climate change pivot so that it becomes cheaper for British consumers and businesses to invest in green technology than remain with the status quo.This does not recognize that most renewable energy technology currently focuses on generating electricity, while the crisis is in liquid fuels for transportation, and it also ignores the likely over supply of natural gas which is separate that price from the rising price of oil over the coming years. Tsk!

He said that if oil only reaches $108 a barrel by 2020 as predicted by the US Department of Energy, which would also lead to higher gas prices, then "the UK consumer will win hands down". He said the UK consumer would be "paying less through low-carbon policies than they would pay for fossil fuel policies".

The current situation in the MENA countries is in such a state of flux, and the impacts barely recognized as yet, that it is becoming even more difficult to have any confidence that the predictions of performance that were being used only a couple of months ago will continue to have much validity in predicting what is likely to occur even in the relatively short term future.

Read more!

Labels:

Angola,

consumption rates,

Libya,

LNG,

natural gas production,

Nigeria,

oil production,

United Kingdom

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Natural Gas - Liquid from abroad

Most frequently these days questions about the likely price and supply of natural gas, focus on the production that is likely from the gas shale deposits around the county. Natural gas drilling rigs are being shut down in large numbers, the count is now over 50% down, at 790 rigs, over last summer and new well numbers reduced, in order to lower supply levels to that closer to demand. (In passing it is worth commenting that horizontal rigs have not dropped as much as vertical, so that the numbers are now approximately equal). The assumption is that as supply declines, and demand stays relatively robust (this not being one of the global warming years – at least so far) the two will come closer to parity, and prices can be restored. At the EIA meeting, most of the audience seemed to anticipate that this would occur this year, and the latest Natural Gas Weekly Update notes that prices do seem to have reached, at least temporarily, some sort of floor.

One of the questions, going forward, however, relates not to the availability of domestic supply, but rather the supply that might be available from abroad. In the past, with almost all gas being supplied by pipeline, that was not much of an issue, but at present there is a significant growth in the availability of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as both liquefaction facilities and available tanker numbers increase. There is the potential, as this supply increases, and if global demand does not match this increase, given the breadth of the economic turndown, that LNG will be available into the American market at a low enough price that it will keep domestic prices, and thus production, constrained.

LNG facilities are not something that can be put in overnight. As the most recent example in Poland shows current new agreements will lead to facility construction and production that appears in around 2014. The Polish facility is planned to handle 2.5 million tons of LNG, and the company has just contracted to get 1 million tons of that from Qatar. Of course, if the permits are turned down (as happened with the Broadwater application this week, after the Department of Commerce joined the governments of New York and Connecticut in rejecting the plan) then those deliveries become moot, and New England gas prices may continue to stay high. (Depending on what happens with the Marcellus – but we will save that discussion for another day). At least that is a decision – down in Australia there is still some uncertainty over plans for a new liquefaction facility in Western Australia, though given the state of world supply, delays might not be all bad.

There are three major facility costs involved in creating an LNG supply. First the gas has to be cleaned, separated and condensed. This is generally done in facilities geared to produce a set volume a year (defined as a train) so that, for example, the facility at Point Fortin, in Trinidad, is made up of three trains, each of which can produce 3.3 million tons/yr of LNG, and one train that produces 2.4 million tons/yr.

To give some idea of scale LNG imports into Europe in 2008 totalled 44.8 million metric tons, with a capacity of 78 mill tons/yr. Most of the supply has come from Algeria (16 mill), Egypt (4.4 mill) , Nigeria (12.5 mill) and Trinidad and Tobago (4.4 mill). (Source Oil & Gas J Apr. 13, 2009 pp 38 – 48 – sub reqd).

The largest facilities for producing LNG are in Ras Laffan in Qatar. The current facility is being doubled to produce 77 million tons/yr by 2010. At the moment supply from the second train (Qatargas2) is scheduled to go the United Kingdom at the South Hook Terminal at Millford Haven, where it will supply some 20% of the national need.

The LNG has to be transported to the receiving terminals by carrier. There are at present some 151 LNG carriers in service, with an additional 51 under construction. They have a total carrying capacity of some 635 million cu ft. (Natural gas is condensed by a factor of 600 when it is liquefied). There are several sizes of carriers that are available, but they are usually divided into three classes. The largest can carry over 4.2 mcf of LNG (125 carriers); the intermediate between 1.75 and 4.2 mcf (15 carriers); and the smallest below 1.75 mcf (15 carriers). Almost all the new carriers are at the 5 mcf size.

There are eight U.S. facilities that can import LNG and while there are 40 more under consideration, industry analysts predict that at best only 12 of these might be built.

They are located in:

Everett, Massachusetts

Cove Point, Maryland

Elba Island, Georgia

Lake Charles, Louisiana

Gulf Gateway Energy Bridge, Gulf of Mexico

Northeast Gateway, Offshore Boston

Freeport, Texas

Sabine, Louisiana

There is also an export facility in Kenai, Alaska.

The new production coming on line in Qatar is more than the current market can absorb, and the Qatar CEO notes

Since their supply will build over the next three years, while gas shale production remains relatively high, this suggests that American prices will remain lower.

(Note that a metric ton of LNG is equivalent to 48,700 cu.ft. of NG. ) LNG is cooled to – 260 deg F ( - 160 deg C) reducing the volume by 600-fold as it turns liquid.

One of the questions, going forward, however, relates not to the availability of domestic supply, but rather the supply that might be available from abroad. In the past, with almost all gas being supplied by pipeline, that was not much of an issue, but at present there is a significant growth in the availability of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as both liquefaction facilities and available tanker numbers increase. There is the potential, as this supply increases, and if global demand does not match this increase, given the breadth of the economic turndown, that LNG will be available into the American market at a low enough price that it will keep domestic prices, and thus production, constrained.

LNG facilities are not something that can be put in overnight. As the most recent example in Poland shows current new agreements will lead to facility construction and production that appears in around 2014. The Polish facility is planned to handle 2.5 million tons of LNG, and the company has just contracted to get 1 million tons of that from Qatar. Of course, if the permits are turned down (as happened with the Broadwater application this week, after the Department of Commerce joined the governments of New York and Connecticut in rejecting the plan) then those deliveries become moot, and New England gas prices may continue to stay high. (Depending on what happens with the Marcellus – but we will save that discussion for another day). At least that is a decision – down in Australia there is still some uncertainty over plans for a new liquefaction facility in Western Australia, though given the state of world supply, delays might not be all bad.

There are three major facility costs involved in creating an LNG supply. First the gas has to be cleaned, separated and condensed. This is generally done in facilities geared to produce a set volume a year (defined as a train) so that, for example, the facility at Point Fortin, in Trinidad, is made up of three trains, each of which can produce 3.3 million tons/yr of LNG, and one train that produces 2.4 million tons/yr.

To give some idea of scale LNG imports into Europe in 2008 totalled 44.8 million metric tons, with a capacity of 78 mill tons/yr. Most of the supply has come from Algeria (16 mill), Egypt (4.4 mill) , Nigeria (12.5 mill) and Trinidad and Tobago (4.4 mill). (Source Oil & Gas J Apr. 13, 2009 pp 38 – 48 – sub reqd).

The largest facilities for producing LNG are in Ras Laffan in Qatar. The current facility is being doubled to produce 77 million tons/yr by 2010. At the moment supply from the second train (Qatargas2) is scheduled to go the United Kingdom at the South Hook Terminal at Millford Haven, where it will supply some 20% of the national need.

The LNG has to be transported to the receiving terminals by carrier. There are at present some 151 LNG carriers in service, with an additional 51 under construction. They have a total carrying capacity of some 635 million cu ft. (Natural gas is condensed by a factor of 600 when it is liquefied). There are several sizes of carriers that are available, but they are usually divided into three classes. The largest can carry over 4.2 mcf of LNG (125 carriers); the intermediate between 1.75 and 4.2 mcf (15 carriers); and the smallest below 1.75 mcf (15 carriers). Almost all the new carriers are at the 5 mcf size.

There are eight U.S. facilities that can import LNG and while there are 40 more under consideration, industry analysts predict that at best only 12 of these might be built.

They are located in:

Everett, Massachusetts

Cove Point, Maryland

Elba Island, Georgia

Lake Charles, Louisiana

Gulf Gateway Energy Bridge, Gulf of Mexico

Northeast Gateway, Offshore Boston

Freeport, Texas

Sabine, Louisiana

There is also an export facility in Kenai, Alaska.

The new production coming on line in Qatar is more than the current market can absorb, and the Qatar CEO notes

“For the shorter term, I don’t think the UK will be able to take 16 million tons,” al-Suwaidi said. “Anything the UK cannot absorb, we will have to find a market for.”

Since their supply will build over the next three years, while gas shale production remains relatively high, this suggests that American prices will remain lower.

The consumption of petroleum products in Japan, the world's biggest buyer of LNG, is projected to fall 4.7 per cent in the year starting this month, according to the Institute of Energy Economics Japan, a government-run think tank. The global recession has reduced electricity use in Japan.

LNG producers probably will ship excess supply to North America, which might prevent a recovery in US natural-gas prices next year, Law said.

(Note that a metric ton of LNG is equivalent to 48,700 cu.ft. of NG. ) LNG is cooled to – 260 deg F ( - 160 deg C) reducing the volume by 600-fold as it turns liquid.

Read more!

Labels:

Algeria,

Egypt,

LNG,

Nigeria,

Qatar,

South Hook,

Trinidad and Tobago

Wednesday, April 8, 2009

2009 Energy Conference - Meeting the growing demand for liquids

The third session of the conference dealt with either electrical power generation or transportation fluids. In reality that meant, for the second topic, that the topic was crude oil. Moderated by Glen Sweetnam the panel included Eduardo Gonzalez-Pier of PEMEX, DavidKnapp of the Energy Intelligence Group and Fareed Mohamedi of PFC Energy.

The panel moved around the world looking at the prospects for increasing production from the major producers of oil, dividing them into those whose production can be anticipated to increase, and those who are known to be declining in production. The list of those increasing included the USA, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Canada, Algeria, Nigeria Iraq and Kuwait. For those who are wondering if time has moved backwards, or question whether the world has changed enough that this site is no longer dealing with a real concern – the anticipated increase in production in the United States is relatively small and transient. It is coming from the increase in production that is being achieved by the rigs in the deep water of the Gulf, and is sadly not going to take us back to the days when the country produced more than anyone else. The panel also looked at the change in the nature of production since IOCs were replaced in the scale of greatest production by NOCs. The panel did not seem to feel that this would, in itself, make much difference since, in the end, as oil fields decline the NOCs would have to engage with the IOCs in order to acquire the technology (see closing story at the end of the post) that would allow them to enhance recovery from their remaining reserve.

I started out in the other panel (which was talking about transmission lines) and did not come into the room until they were talking about Mexican production. I did not initially know the background of the speaker, (it was Eduardo) who, shortly after I arrived, commented that Pemex expected to stabilize production at existing levels for the next several years. He and the other two speakers talked about the increase in production from KMZ that would offset the Cantarell decline, and that there would be the longer term production from Chicontepec that would continue this stable production for the next few years. Somehow my concentration wandered after this, and so my reporting on this session (that occurred just after a brisk walk and lunch) may be a little less that all that was said.

The panel opinion on Venezuela was not promising (pessimistic was the word used) with significant questions on sustainability, although there is the hope that the majors would be reinvited back with renegotiations to bring production back to a more reasonable level. (Taken with the discussion on Mexico this also encouraged me to enter a dream-like state).

They generally viewed Brazil, and Petrobras, as a success. Nigeria was described as a failed state, though there were some attempts to distinguish the success of some of the production from the troubles that were occurring because of the insurrection in the country. Looking at Algeria the debate focused on the natural gas business and there was some debate on the hydrocarbon law in that country.

Libya is a different case. Having grown accustomed to a lack of external funds and lower levels of income, the country is quite able to weather the current cut back in oil prices and the Government has enough revenue at the moment and thus is not under pressure to export more. Because of a lack of investment over the past decades, the opportunities to increase production, particularly through secondary and tertiary recovery is considered gigantic, and thus the overall view of Libyan production has to be optimistic. (It is interesting to note that China is reported to be going after the Canadian interests in Libya).

Looking at the countries of the Middle East, Iraq and Kuwait can be expected to remain relatively stable in production, though with some potential for increase. However, as with a countries in the region, the questionability of the reserve values quoted keeps coming up. (In a later question the panel felt no compunction in accepting Saudi figures for their reserves and had no concern that the values had not changed over the years. They did recognize, however, that in contrast to other countries in the Middle East they counted proved and probable in reserves, not just proved). Kuwait is “muddling through.” The damage done to the Burgan field by the Iraqi army in their retreat after the first Gulf War did more damage to the field than was at first realized. Instead of this being a field that produced under its own pressure, pressure now has to be supplied to the field to get the production out, and this has opened a need for new technology that has not yet been realized. Kuwait can, however, live on $20 oil prices.