Showing posts with label air content. Show all posts

Showing posts with label air content. Show all posts

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

Waterjetting 11a - More thoughts on Abrasive

In the last post I mentioned that the abrasive particles, which are fed into a high-pressure waterjet stream to form the Abrasive WaterJet (AWJ) cutting tool, can be significantly crushed when mixing with the high-pressure waterjet, and before they leave the mixing chamber. Because of this - depending on the application - the choice of abrasive can play a significant role in how well the AWJ performs. I have mentioned a number of times that the Waterjet Lab is located at Missouri University of Science and Technology. That meant (apropos “show me”) that it was an appropriate place to run comparative tests between different abrasives to find which is the best.

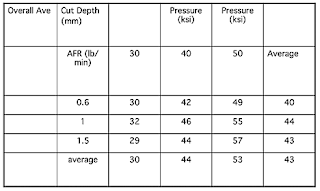

It turns out that there is no one single answer to that question, since the abrasive that was the most economical and effective to use in one case does not necessarily give the best results in another. Which brings me to the first point in today’s post. It is relatively easy to get small samples of the different abrasives that might be used in a given job. Setting up a small series of test runs, in which the different abrasives being considered, are fed to the nozzle and use to cut standard cuts into test samples, is a relatively easy way to find out which is the best abrasive for that particular material and cutting path. However it is best not to use only a single test run, we would generally run a series with three different jet pressures and three different abrasive feed rates.

Figure 1. Table showing the change in optimal Abrasive Feed Rate (AFR) on cut depth at different pressures.

By bracketing the range that is likely to have the best concentration of abrasive for each pressure (which is not at the same abrasive feed rate, or AFR) the best result can be found for each different pressure value, and the most economical and effective choice for the task in hand can be quickly found. It is important to include economics in the evaluation, since there have been a number of cases we looked at where the most effective choice for abrasive in terms of giving the fastest clean cut was not that much more effective than the second place abrasive, and that alternative was sufficiently cheaper that it made more sense to use it.

The pricing of abrasive, however, is not something that it is easy to generalize over, since there are a number of different factors that come into play, depending where in the country you are located. As a rough guidance, however, we have found that garnet is a more universal cutting abrasive than most others, with less extraneous “issues”, and while it can be less effective than other selections in some conditions, in general it will cut more materials effectively and economically than its challengers. Further mined garnet, in general, performs better than alluvial garnet since it does not have the degree of damage within the particles that leads them to fragment more easily in the mixing chamber.

There are, however, more factors that just the abrasive type that have to be considered. There include the particle size, and range, and then, as noted in the table, there is the selection of the AFR to match the cutting conditions on the table.

One of the more neglected factors relates to the amount of air that is used to carry the abrasive from the hopper into the mixing chamber. The person who did more to shine a light into this corner of the technology was Tabitz, in France. (Tabitz, Schmidt, Parsy, Abriak, and Thery “Effect of Air on accceleration process in AWJ entrainment system, 12th ISJCT, Rouen, 1994 p 47 - 58.)

Because abrasive can cut into the parts of the flow meter, the equipment that they used included a trap between the hopper and the mixing chamber, where the particles could be collected, while the air passed forward to be measured and enter the mixing chamber.

Figure 2. Apparatus used by Tabitz in measuring the air flow to the cutting head and mixing chamber. (ibid)

The results from the measurement showed that as the jet pressure increased, so for that particular nozzle design, did the amount of air that was being drawn into the chamber – although you may note that it begins to reach a constant volume as the pressure approaches 280 MPa (40,000 psi).

Figure 3. Effect of increased jet pressure on the amount of air drawn into the nozzle, as a percentage of the total volume of the resulting jet. (Tabitz et al)

The problem that this relatively large volume of air presents is that it has to be accelerated at the same time as the energy in the jet is being transferred to the abrasive particles. The larger the amount of air in the mix, then the greater the amount of water energy that has to be diverted into accelerating the air. This leaves less energy available to accelerate the abrasive itself.

Tabitz modeled the result with a simulation in a computer program, which illustrates, for different abrasive feed rates, how the average abrasive particle velocity falls as the amount of air in the mix increases:

Figure 4. Simulated effect of an increase in air flow on the reduction in average abrasive particle velocity (after Tabitz et al).

Placing small instruments in front of abrasive-laden waterjets can lead to a relatively short life for those instruments, and measurements of actual particle velocities, though they have been made by a number of researchers, have not been as comprehensive as the above chart might indicate.

Nevertheless there is some indication that the above curves are accurate in principle, if not totally real. A jet with very little air might accelerate particles to 1,880 ft/sec, for example. However with 70% air in the mix, then the particle velocity might fall to 1,700 ft/sec, and with 95% of the jet made up of air, then the abrasive particle speed may fall to 1,200 ft/sec. Part of the difficulty in assessment is because of the very short time interval in which the abrasive particles are accelerated while in the mixing chamber. Because the rate of acceleration of the particles is inversely related to their size. Smaller particles are accelerated faster. And this is the counter to the point that was made in the last post about smaller particles cutter less efficiently than larger ones.

Part of the reason for this is that the smaller particles are decelerated faster in air than larger particles. The results of this in terms of cutting power is one of the areas that still requires more research. If, for example, smaller particles are used in an application (for example to achieve a finer detail in the surface cutting) then the effective range of the jet can become smaller than with larger particles. There are some caveats to that statement, and I will go into some of that explanation in the next post.

It turns out that there is no one single answer to that question, since the abrasive that was the most economical and effective to use in one case does not necessarily give the best results in another. Which brings me to the first point in today’s post. It is relatively easy to get small samples of the different abrasives that might be used in a given job. Setting up a small series of test runs, in which the different abrasives being considered, are fed to the nozzle and use to cut standard cuts into test samples, is a relatively easy way to find out which is the best abrasive for that particular material and cutting path. However it is best not to use only a single test run, we would generally run a series with three different jet pressures and three different abrasive feed rates.

Figure 1. Table showing the change in optimal Abrasive Feed Rate (AFR) on cut depth at different pressures.

By bracketing the range that is likely to have the best concentration of abrasive for each pressure (which is not at the same abrasive feed rate, or AFR) the best result can be found for each different pressure value, and the most economical and effective choice for the task in hand can be quickly found. It is important to include economics in the evaluation, since there have been a number of cases we looked at where the most effective choice for abrasive in terms of giving the fastest clean cut was not that much more effective than the second place abrasive, and that alternative was sufficiently cheaper that it made more sense to use it.

The pricing of abrasive, however, is not something that it is easy to generalize over, since there are a number of different factors that come into play, depending where in the country you are located. As a rough guidance, however, we have found that garnet is a more universal cutting abrasive than most others, with less extraneous “issues”, and while it can be less effective than other selections in some conditions, in general it will cut more materials effectively and economically than its challengers. Further mined garnet, in general, performs better than alluvial garnet since it does not have the degree of damage within the particles that leads them to fragment more easily in the mixing chamber.

There are, however, more factors that just the abrasive type that have to be considered. There include the particle size, and range, and then, as noted in the table, there is the selection of the AFR to match the cutting conditions on the table.

One of the more neglected factors relates to the amount of air that is used to carry the abrasive from the hopper into the mixing chamber. The person who did more to shine a light into this corner of the technology was Tabitz, in France. (Tabitz, Schmidt, Parsy, Abriak, and Thery “Effect of Air on accceleration process in AWJ entrainment system, 12th ISJCT, Rouen, 1994 p 47 - 58.)

Because abrasive can cut into the parts of the flow meter, the equipment that they used included a trap between the hopper and the mixing chamber, where the particles could be collected, while the air passed forward to be measured and enter the mixing chamber.

Figure 2. Apparatus used by Tabitz in measuring the air flow to the cutting head and mixing chamber. (ibid)

The results from the measurement showed that as the jet pressure increased, so for that particular nozzle design, did the amount of air that was being drawn into the chamber – although you may note that it begins to reach a constant volume as the pressure approaches 280 MPa (40,000 psi).

Figure 3. Effect of increased jet pressure on the amount of air drawn into the nozzle, as a percentage of the total volume of the resulting jet. (Tabitz et al)

The problem that this relatively large volume of air presents is that it has to be accelerated at the same time as the energy in the jet is being transferred to the abrasive particles. The larger the amount of air in the mix, then the greater the amount of water energy that has to be diverted into accelerating the air. This leaves less energy available to accelerate the abrasive itself.

Tabitz modeled the result with a simulation in a computer program, which illustrates, for different abrasive feed rates, how the average abrasive particle velocity falls as the amount of air in the mix increases:

Figure 4. Simulated effect of an increase in air flow on the reduction in average abrasive particle velocity (after Tabitz et al).

Placing small instruments in front of abrasive-laden waterjets can lead to a relatively short life for those instruments, and measurements of actual particle velocities, though they have been made by a number of researchers, have not been as comprehensive as the above chart might indicate.

Nevertheless there is some indication that the above curves are accurate in principle, if not totally real. A jet with very little air might accelerate particles to 1,880 ft/sec, for example. However with 70% air in the mix, then the particle velocity might fall to 1,700 ft/sec, and with 95% of the jet made up of air, then the abrasive particle speed may fall to 1,200 ft/sec. Part of the difficulty in assessment is because of the very short time interval in which the abrasive particles are accelerated while in the mixing chamber. Because the rate of acceleration of the particles is inversely related to their size. Smaller particles are accelerated faster. And this is the counter to the point that was made in the last post about smaller particles cutter less efficiently than larger ones.

Part of the reason for this is that the smaller particles are decelerated faster in air than larger particles. The results of this in terms of cutting power is one of the areas that still requires more research. If, for example, smaller particles are used in an application (for example to achieve a finer detail in the surface cutting) then the effective range of the jet can become smaller than with larger particles. There are some caveats to that statement, and I will go into some of that explanation in the next post.

Read more!

Saturday, June 29, 2013

Waterjetting 10d - Abrasive sizing

Over the past 30 years abrasive waterjet cutting has become an increasingly useful tool for cutting a wide range of materials, of varying thickness and strength. However, as the range of applications for the tool has grown, so the requirements for improved performance have also risen. Before being able to make a better quality cut there had to be a better understanding of how abrasive waterjet cutting works, so that the improvements could be made.

Figure 1. Some factors that affect the cutting performance of an abrasive waterjet (After Mazurkiewicz)

This understanding has not been easy to develop, since there are many different factors that all affect how well the cutting process takes place. Consider, first of all, the process of getting the abrasive up to the fastest speed possible. And for the purpose of discussion I am going to use a “generic” mixing chamber and focusing tube nozzle for the following discussion.

Figure 2. Simplified sketch of a mixing chamber and focusing tube nozzle used in adding abrasive to a high pressure waterjet.

As high-pressure water flows through the small orifice (which in the sketch was historically made of sapphire) it enters a larger mixing chamber and creates a suction that will pull abrasive into the mixing chamber through the side passage. That side passage is connected, through a tube, to a form of abrasive feed mechanism, that I will not discuss in detail today.

However the abrasive does not flow into the mixing chamber by itself. Rather it is transported into the mixing chamber using a fluid carrier. In the some of the earliest models of abrasive waterjet systems water was used as the carrier fluid to bring the abrasive into the mixing chamber. This, as a general rule, turned out to be a mistake.

The problem is that, within the mixing chamber, the energy that comes into the chamber with the high-pressure water has to mix, not only with the abrasive, but also with the fluid that carried the abrasive into the chamber. Water is heavier than air, and so if water is the carrier fluid, then it will absorb more of the energy that is available, with the result that there is less for the abrasive, which – as a result – does not move as quickly and therefore does not cut as well. The principle was first discussed by John Griffiths at the 2nd U.S. Waterjet Conference, although he was discussing abrasive use in cleaning at the time.

Figure 3 Difference in performance of water acting to carry the abrasive to the mixing chamber (wet feed) in contrast with the use of air as the carrier fluid. (Griffiths, J.J., "Abrasive Injection Usage in the United Kingdom," 2nd U.S. Waterjet Conference, May, 1983, Rolla, MO, pp. 423 - 432.)

Note that this is not the same as directly mixing the abrasive into the waterjet stream under pressure – abrasive slurry jetting – which I will discuss in later posts.

The difference between the two ways of bringing the abrasive to the mixing chamber is clear enough that almost from the beginning only air has been considered as the carrier to bring the abrasive into the mixing chamber. However there is the question as to how much air is enough, how much abrasive should be added, and how effectively the mixing process takes place.

In the earlier developments the equipment available restricted the range of pressures and flow rates at which the high pressure water could be supplied, and these limits bounded early work on the subject.

One early observation, however, was that the size of the abrasive that was being fed into the mixing chamber was not the average size of the abrasive after cutting was over. (At that time steel was not normally used as a cutting abrasive). Because the fracture of the abrasive into smaller pieces might mean that the cutting process became less effective, Greg Galecki and Marian Mazurkiewicz began to measure particle sizes, at different points in the process. (Galecki, G., Mazurkiewicz, M., Jordan, R., "Abrasive Grain Disintegration Effect During Jet Injection," International Water Jet Symposium,Beijing, China, September, 1987, pp. 4-71 - 4-77.)

For example, by firing the abrasive-laden jet along the axis of a larger plastic tube (here opened to show the construction) the abrasive would, after leaving the nozzle, decelerate and settle into the bottom of the tube, without further break-up, and without damage to the tube. Among other results this allowed a measure of how fast the particles leave the nozzle, since the faster they were moving, then the further they would carry down the pipe.

Figure 4. Test to examine particle size and travel distance, after leaving the AWJ nozzle at the left of the picture. The containing tube has divisions every foot, and small holes over blue containers, so that the amount caught in every foot could be collected and measured.

For one particular test the abrasive going into the system was carefully screened to be lie in the size range between 170 and 210 microns. It was then fed into a 30,000 psi waterjet at a feed rate of 0.6 lb/minute. The particles were captured, after passing through the mixing chamber, but before they could cut anything, by using the tube shown in Figure 4. The size of the particles was then measured, and plotted as a cumulative percentage adding the percentages found at each sieve size over the range to the 210 micron size of the starting particles.

Figure 5. Average size of particles after passing through a mixing chamber and exiting into a capture tube, without further damaging impact.

The horizontal line shows the point where 50% of the abrasive (by weight) had accumulated, and the vertical line shows that this is at a particle size of 140 microns. Thus, just in the mixing process alone energy is lost in mixing the very fast moving water, with the initially much slower moving abrasive.

And, as an aside, this is where the proper choice of abrasive becomes an important part of an effective cutting operation. Because the distribution of the curve shown in figure 5 will change, with abrasive type, size, concentration added, as well as the pressure and flow rate of the nozzle through which the water enters the mixing chamber.

I will have more to discuss on this in the next post, but will leave you with the following result. After we had run the tests which I just mentioned, we collected the abrasive in the different size ranges. Then we used those different size ranges to see how well the abrasive cut. This was one of the results that we found.

Figure 6. The effect of the size of the feed particles into the abrasive cutting system on the depth of cut which the AWJ achieved.

You will note that down to a size of around 100 microns the particle size did not make any significant difference, but that once the particle size falls below that range, then the cutting performance degrades considerably. (And if you go back to figure 5, you will note that about 30% of the abrasive fell into that size range, after the jet had left the mixing chamber).

Figure 1. Some factors that affect the cutting performance of an abrasive waterjet (After Mazurkiewicz)

This understanding has not been easy to develop, since there are many different factors that all affect how well the cutting process takes place. Consider, first of all, the process of getting the abrasive up to the fastest speed possible. And for the purpose of discussion I am going to use a “generic” mixing chamber and focusing tube nozzle for the following discussion.

Figure 2. Simplified sketch of a mixing chamber and focusing tube nozzle used in adding abrasive to a high pressure waterjet.

As high-pressure water flows through the small orifice (which in the sketch was historically made of sapphire) it enters a larger mixing chamber and creates a suction that will pull abrasive into the mixing chamber through the side passage. That side passage is connected, through a tube, to a form of abrasive feed mechanism, that I will not discuss in detail today.

However the abrasive does not flow into the mixing chamber by itself. Rather it is transported into the mixing chamber using a fluid carrier. In the some of the earliest models of abrasive waterjet systems water was used as the carrier fluid to bring the abrasive into the mixing chamber. This, as a general rule, turned out to be a mistake.

The problem is that, within the mixing chamber, the energy that comes into the chamber with the high-pressure water has to mix, not only with the abrasive, but also with the fluid that carried the abrasive into the chamber. Water is heavier than air, and so if water is the carrier fluid, then it will absorb more of the energy that is available, with the result that there is less for the abrasive, which – as a result – does not move as quickly and therefore does not cut as well. The principle was first discussed by John Griffiths at the 2nd U.S. Waterjet Conference, although he was discussing abrasive use in cleaning at the time.

Figure 3 Difference in performance of water acting to carry the abrasive to the mixing chamber (wet feed) in contrast with the use of air as the carrier fluid. (Griffiths, J.J., "Abrasive Injection Usage in the United Kingdom," 2nd U.S. Waterjet Conference, May, 1983, Rolla, MO, pp. 423 - 432.)

Note that this is not the same as directly mixing the abrasive into the waterjet stream under pressure – abrasive slurry jetting – which I will discuss in later posts.

The difference between the two ways of bringing the abrasive to the mixing chamber is clear enough that almost from the beginning only air has been considered as the carrier to bring the abrasive into the mixing chamber. However there is the question as to how much air is enough, how much abrasive should be added, and how effectively the mixing process takes place.

In the earlier developments the equipment available restricted the range of pressures and flow rates at which the high pressure water could be supplied, and these limits bounded early work on the subject.

One early observation, however, was that the size of the abrasive that was being fed into the mixing chamber was not the average size of the abrasive after cutting was over. (At that time steel was not normally used as a cutting abrasive). Because the fracture of the abrasive into smaller pieces might mean that the cutting process became less effective, Greg Galecki and Marian Mazurkiewicz began to measure particle sizes, at different points in the process. (Galecki, G., Mazurkiewicz, M., Jordan, R., "Abrasive Grain Disintegration Effect During Jet Injection," International Water Jet Symposium,Beijing, China, September, 1987, pp. 4-71 - 4-77.)

For example, by firing the abrasive-laden jet along the axis of a larger plastic tube (here opened to show the construction) the abrasive would, after leaving the nozzle, decelerate and settle into the bottom of the tube, without further break-up, and without damage to the tube. Among other results this allowed a measure of how fast the particles leave the nozzle, since the faster they were moving, then the further they would carry down the pipe.

Figure 4. Test to examine particle size and travel distance, after leaving the AWJ nozzle at the left of the picture. The containing tube has divisions every foot, and small holes over blue containers, so that the amount caught in every foot could be collected and measured.

For one particular test the abrasive going into the system was carefully screened to be lie in the size range between 170 and 210 microns. It was then fed into a 30,000 psi waterjet at a feed rate of 0.6 lb/minute. The particles were captured, after passing through the mixing chamber, but before they could cut anything, by using the tube shown in Figure 4. The size of the particles was then measured, and plotted as a cumulative percentage adding the percentages found at each sieve size over the range to the 210 micron size of the starting particles.

Figure 5. Average size of particles after passing through a mixing chamber and exiting into a capture tube, without further damaging impact.

The horizontal line shows the point where 50% of the abrasive (by weight) had accumulated, and the vertical line shows that this is at a particle size of 140 microns. Thus, just in the mixing process alone energy is lost in mixing the very fast moving water, with the initially much slower moving abrasive.

And, as an aside, this is where the proper choice of abrasive becomes an important part of an effective cutting operation. Because the distribution of the curve shown in figure 5 will change, with abrasive type, size, concentration added, as well as the pressure and flow rate of the nozzle through which the water enters the mixing chamber.

I will have more to discuss on this in the next post, but will leave you with the following result. After we had run the tests which I just mentioned, we collected the abrasive in the different size ranges. Then we used those different size ranges to see how well the abrasive cut. This was one of the results that we found.

Figure 6. The effect of the size of the feed particles into the abrasive cutting system on the depth of cut which the AWJ achieved.

You will note that down to a size of around 100 microns the particle size did not make any significant difference, but that once the particle size falls below that range, then the cutting performance degrades considerably. (And if you go back to figure 5, you will note that about 30% of the abrasive fell into that size range, after the jet had left the mixing chamber).

Read more!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)